Try Wildlife Refuges Off-Season

Fall, winter and spring can provide the best beach time, especially when a pandemic requires us to keep our distance from each other.

Sunrises come later and sunsets come earlier. Dolphins still play in the waves and crabs scuttle across the beach.

For bikers, hikers, paddlers and surf fishers, the weather can be balmy or brisk, but not suffocating, and for birders, it’s the best time of year.

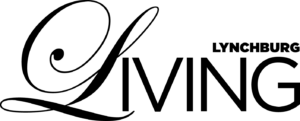

Virginia’s Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1938 to protect migratory and wintering waterfowl, supports up to 10,000 snow geese and a large variety of ducks and other waterfowl during the annual peak migration, usually in December and January.

The refuge encompasses nearly 10,000 acres of beach, dunes, woodlands of live oak and loblolly pines, farm fields and marshes, along with the freshwaters of Back Bay.

Located just north of North Carolina, this coastal refuge also provides habitat for threatened and endangered species including sea turtles and piping plovers, small shorebirds that are declining rapidly.

More than 300 species of birds have been observed at Back Bay, primarily during winter months. Mammals include river otters, mink, opossums, raccoons, foxes, and white-tailed deer.

Canals provide a glimpse of venomous cottonmouth snakes, swimming across the water, along with brown and northern watersnakes. On warm days, a variety of turtles, including red-bellied, painted, eastern mud, and snapping, may warm themselves on logs or lurk beneath the surface.

This slender strip of land is covered in common reeds, which can reach 15 feet in height, providing cover for many animals, including humans as they stroll along boardwalks.

Groundsel or sea myrtle, with lovely white flowers, attracts butterflies and other pollinators, and provides seeds for birds.

Wax myrtle, a traditional source of wax for bayberry candles, is a favorite of the

wintering yellow-rumped warbler.

On a visit in October, the refuge was full of yellow in the form of goldenrod and smooth beggarticks. Great Plains lady’s tresses, a spiky plant with white blossoms, and blue mistflowers, could be spied along the trail.

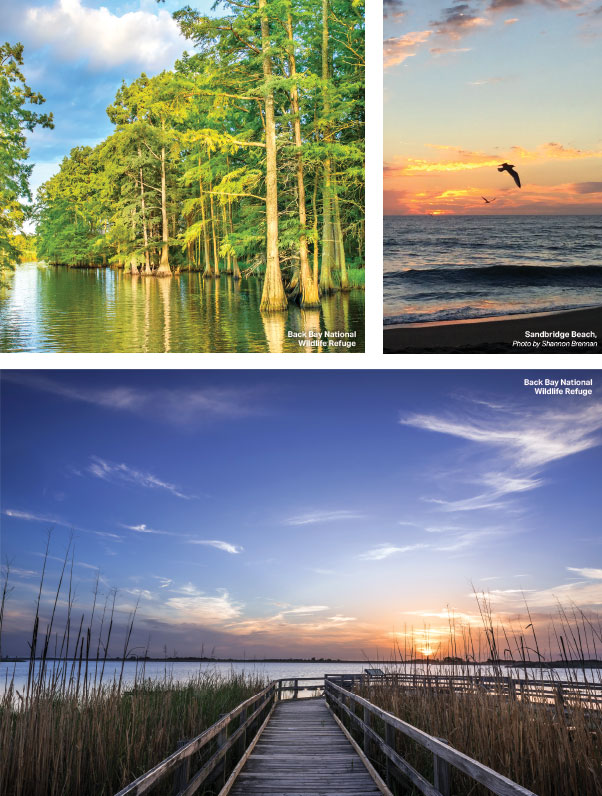

Entrance to the refuge is just south of Sandbridge, a long narrow barrier island, 16 miles south of Virginia Beach.

We stayed at an Airbnb at Surfside at Sandbridge, an RV resort, just north of the refuge and enjoyed views from our canal-side porch. For dinner, we ordered takeout from the nearby Baja Restaurant with its many seafood options. For a breakfast treat, the homemade doughnuts at the Sandbridge Seaside Market are not to be missed.

A short stroll from our Airbnb mobile home took us to the Atlantic Ocean, where only a handful of people splashed along the water’s edge, tossed in a fishing line, or flew kites.

A five-minute car ride took us to the entrance to Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Outdoor trails are open a half hour before sunrise and a half hour after sunset, and there is no entry fee from Nov. 1 to April 1.

All vehicles must park at the visitor center, which was closed due to COVID-19. To protect wildlife, no dogs are allowed in the refuge.

From the parking area, folks can walk along boardwalks to Back Bay or to the ocean. You can also bike or hike the four-mile trail to False Cape State Park or continue to the North Carolina line for an 8.8-mile trek one-way.

Several adventurous types were backpacking into False Cape, where primitive tent camping is available for a complete getaway.

While at Sandbridge, we couldn’t resist a trip north to Kiptopeke State Park, where the annual hawk migration count was underway. To get to the eastern shore, you must traverse the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, which is an amazing experience in itself.

The Bay Bridge-Tunnel is a four-lane 20-mile-long vehicular toll crossing that provides direct access from southeastern Virginia to the Delmarva Peninsula (Delaware plus the Maryland and Virginia Eastern Shore).

Spectacular views of the Chesapeake Bay along the bridges also offer glimpses of brown pelicans and black-backed gulls, the largest gulls in the world. As you take two plunges under the bay in two separate tunnels, you appreciate the engineering required to disappear under the water as giant cargo ships ply overhead.

As you leave the bridge, you enter the Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge, one of the most important avian migration funnels in North America. This 1,100-acre refuge is the scene of a spectacular drama as millions of songbirds and thousands of monarch butterflies and raptors converge on their journey south. Favorable weather patterns push migrating species through the area in waves.

Numerous tree swallows swirl overhead and monarch butterflies float aloft. Protected habitats such as these provide critical stopover areas where birds, monarchs, and dragonflies can rest and feed before resuming their arduous journey.

We saw several sharp-shinned and a handful of cooper’s hawks and bald eagles at the refuge before continuing on to Kiptopeke. While it turned out to be a slow day for migrating raptors, we saw hundreds of pine siskins and a dozen red-breasted nuthatches, northern species which only venture south when there is a poor seed crop in Canada.

Another winter getaway awaits near the Maryland state line at Assateague Island National Seashore, famous for its wild ponies and the annual summer roundup at Chincoteague.

To our south, the Outer Banks of North Carolina are also thick with off-season delights. Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge offers some of the best winter birding.

The refuge is 13 miles long and covers 5,834 acres of land, located on the north end of Hatteras Island. The bird list for Pea Island boasts more than 365 species; the wildlife list has 25 species of mammals, 24 of reptiles, and five of amphibians.

These refuges are among 567 National Wildlife Refuges administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, many along the East Coast.

No matter what coastal wildlife refuge or state park you choose, you have many choices for outdoor activities, wildlife viewing, and the peace and serenity of open spaces.